"Lake Charts and Mapping" From The Beginning BREAKLINES

"Lake Charts and Mapping" From The Beginning BREAKLINES

Occasionally, I receive reader comments or questions that require more than a casual answer. On Monday, this email message from Richard Mullet was one of them.

Occasionally, I receive reader comments or questions that require more than a casual answer. On Monday, this email message from Richard Mullet was one of them.

Q) “Jeff, I have enjoyed following you as well as others in trying to improve my fishing skills. One thing that has baffled me for a long time is how to read a lake map correctly. I hear people using terms like breaks, breaklines and that one should fish above the breaks, below the breaks, follow the break lines, fish the flats etc etc.!

I am confused by all that terminology. What exactly is a break? How is a flat defined? Is (the area) where the weeds stop considered (to be) the break line? I have maps on my electronics, and I see the depth lines. Is each line described as a break or break line every time it changes from 10 to 12 feet for example? Could you direct me to a source where I can learn what all these terms mean and how I might apply them? I want to learn but have never heard anyone actually define in a way so my simple brain can comprehend! Thanks for all you do. You are one of the best! Thank you, Richard Mullet”

A) Richard, Wow, as my grandmother used to say, “that’s a mouthful!”

First off, thank you for the vote of confidence in my ability to deliver meaningful answers to your questions. These days, so many of us ‘fishing educators” make a false assumption that folks already “know the basics” of fishing, including how to read and translate information from charts, fishing graphs and the like. Your questions remind me that I can do a better job of relaying understandable information in my daily reports and fishing articles. So, I’ve decided to start here, taking your list and offering illustrations every day, until we’ve covered your list entirely.

During the course of this project, I divided each item into individual, search-able sections. Below you'll see a bullet point list that allows readers to jump to any section. Don't see a definition that suits your needs? As always, anglers are invited to contribute, ask questions or comment about all FishRapper articles. Use the links below to contact us any time!

Maps and Charts Interpretation Sections

- Maps and Charts Interpretation: BREAKLINES

- Maps and Charts Interpretation: SOFT BREAKS

- Maps and Charts Interpretation: SUBMERGED SHORELINE POINTS

- Maps and Charts Interpretation: MID LAKE BARS

- Maps and Charts Interpretation: MAIN LAKE FLATS

- Maps and Charts Interpretation: WEEDLINES vs WEED FLATS

- Maps and Charts Interpretation: BREAKLINES A CLOSER LOOK

- Maps and Charts Interpretation: MID-LAKE HUMPS

BREAKLINE: Is a term we often use to identify a notable change in the water’s depth. Sometimes, folks refer to a breakline as a “Drop-Off” too, and either term is accurate in my view. Breaklines do not occur at any particular depth and vary from lake to lake. Most often, lakes in our region have more than one drop off, or break line. On Leech Lake, the one I’ve chosen to illustrate for this project, there are shallow 4-to-8-foot deep breaklines adjacent to the shoreline, mid-depth breaks from 12 to about 20 feet, and then deeper breaks that lead into the lakes deepest, main basin water.

BREAKLINE: Is a term we often use to identify a notable change in the water’s depth. Sometimes, folks refer to a breakline as a “Drop-Off” too, and either term is accurate in my view. Breaklines do not occur at any particular depth and vary from lake to lake. Most often, lakes in our region have more than one drop off, or break line. On Leech Lake, the one I’ve chosen to illustrate for this project, there are shallow 4-to-8-foot deep breaklines adjacent to the shoreline, mid-depth breaks from 12 to about 20 feet, and then deeper breaks that lead into the lakes deepest, main basin water.

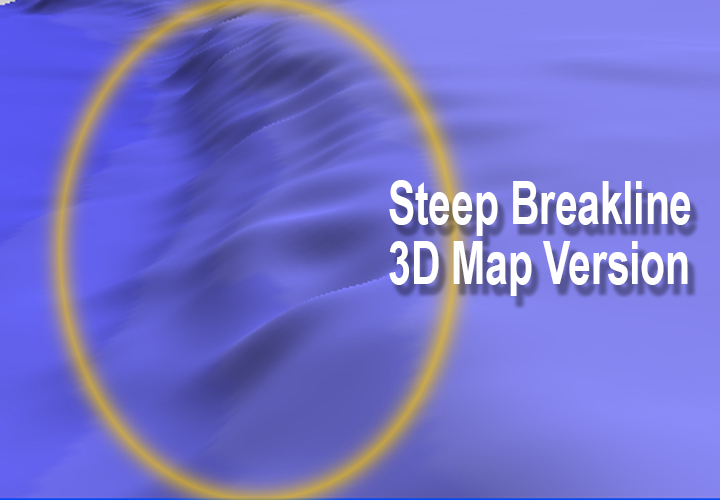

In today’s illustration (Upper Left), I’ve selected a “Sharp or Hard Break” that leads into the deep section of water between Stony and Ottertail Points known to many as “Paris Trench”. In this region, the water depths change quickly starting at about 16 feet, and dropping into 35 feet deep, or so. On the map, the depth lines appear close together, and informs us to expect a sharp drop off, or ledge where depths will change rapidly. The closer (tighter) these depth lines appear on your map, the sharper, or more well defined the drop off will be.

The 3D insert (Lower Right), shows what the contour looks like under the surface, and hopefully, helps clarify the description even more.

"Lake Charts and Mapping" From The Beginning SOFT BRFEAKS

"Lake Charts and Mapping" From The Beginning SOFT BRFEAKS

Yesterday, in response to a reader inquiry, I started a lake map interpretation project. If you missed seeing it, scroll down the page to start from the beginning or click here for the full report >> Leech Lake Fishing Maps and Charts 01-22-2025

In today’s report, I’ve included these images of a chart from the same area, just off of Stony Point on Leech Lake, that shows what a soft, or slow-tapering break line looks like.

In today’s report, I’ve included these images of a chart from the same area, just off of Stony Point on Leech Lake, that shows what a soft, or slow-tapering break line looks like.

Notice how much further the depth lines are spaced compared to the tightly gathered spacing from yesterday’s image of a sharp breakline. Slow tapering drop off areas like these can be more difficult to notice on the electronics in your boat, but don’t overlook them, they are important! Fish that roam for forage like walleyes, perch and sometimes crappies, use these slow tapering breaks when they’re feeding. When scoping out complex structures, look for areas like these that lay adjacent to other structures like points, humps and rock piles.

Speaking of points, that’s where we’ll pick up the discussion tomorrow. I’ll offer illustrations that show what a “point” looks like on your map, and under the surface in 3D form. Check back again tomorrow for another pair of illustrations. ![]() — Jeff Sundin, The Early Bird Fishing Guide Office Cell Call or Text 218-245-9858 or Email

— Jeff Sundin, The Early Bird Fishing Guide Office Cell Call or Text 218-245-9858 or Email

January 25, 2025 "Understanding Lake Charts Submerged Shoreline Points"

January 25, 2025 "Understanding Lake Charts Submerged Shoreline Points"

Today, I’m back to the project concerning interpretation of terminology used to describe lake map and charting data. So far, we’ve compared images of steep breaklines, and soft, slow tapering breaklines. Descriptions of both are simple, and straightforward, making interpretation easy. Eventually, we’ll get into more complex and nuance structures, but in the interest of building on a solid foundation, let’s continue with a few more basic structures. Today, let’s talk about submerged, shoreline related points.

Today, I’m back to the project concerning interpretation of terminology used to describe lake map and charting data. So far, we’ve compared images of steep breaklines, and soft, slow tapering breaklines. Descriptions of both are simple, and straightforward, making interpretation easy. Eventually, we’ll get into more complex and nuance structures, but in the interest of building on a solid foundation, let’s continue with a few more basic structures. Today, let’s talk about submerged, shoreline related points.

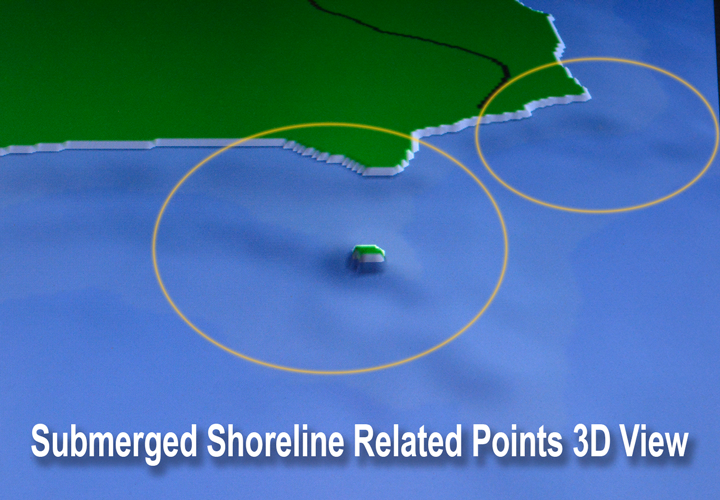

“Shoreline Related” simply means that the structure, or structures are connected directly to the adjacent land mass. So, points can occur not only along the main shoreline of a lake, but also adjacent to islands found further in the lake. Note: Structures that are not directly connected to a land mass will be discussed in upcoming installments.

“Submerged” means that the structure lays beneath the water’s surface and is not visible to the naked eye. As this 3D chart image of Leech Lake’s Two Point reveals, submerged points can be directly connected to a visible, "on-shore structure", but they don’t have to be. At times, you could see a nice looking on shore structure, navigate to it, and discover that there is no submerged cover adjacent to it. Conversely, you will discover numerous submerged points that are connected to a shoreline but have no “visible” connection to it that can be seen above the water line.

“Submerged” means that the structure lays beneath the water’s surface and is not visible to the naked eye. As this 3D chart image of Leech Lake’s Two Point reveals, submerged points can be directly connected to a visible, "on-shore structure", but they don’t have to be. At times, you could see a nice looking on shore structure, navigate to it, and discover that there is no submerged cover adjacent to it. Conversely, you will discover numerous submerged points that are connected to a shoreline but have no “visible” connection to it that can be seen above the water line.

Assessing the potential of points on the lake(s) you fish can be subjective. While points are important structures to many fish species, the individual fish types that they attract will depend on the habitats supported by them. Weeds, rocks, gravel, sand, or marl will provide different species with elements that satisfy their individual preferences. So, once you’ve identified a point on your chart, you’ll need to investigate the habitat to learn whether it supports your desired target species.

That said, there a very few times that I’ve discovered a point on any lake that did not provide a hiding spot for at least a few fish. So, for me, all of them are worth checking out, especially when I’m fishing on a “multi-species” lake. This won’t be the last time you read about submerged points, and we will get into the nuances of habitat types.

Tomorrow, I’ll plan to continue the series by looking at some of the most common, open-water structures. But by now, you may be thinking about specific situations you’ve encountered on the lake. Be sure to let me know, because we don’t have to complete this series in any particular order. I’ll take your questions as they come in, so getting clarification about places you fish can be just days, or hours away. ![]() — Office Call or Text 218-245-9858 or EMAIL or Fishing Reports MN Facebook or Jeff on X

— Office Call or Text 218-245-9858 or EMAIL or Fishing Reports MN Facebook or Jeff on X

"Understanding Lake Charts and Mapping" Mid Lake Bars

"Understanding Lake Charts and Mapping" Mid Lake Bars

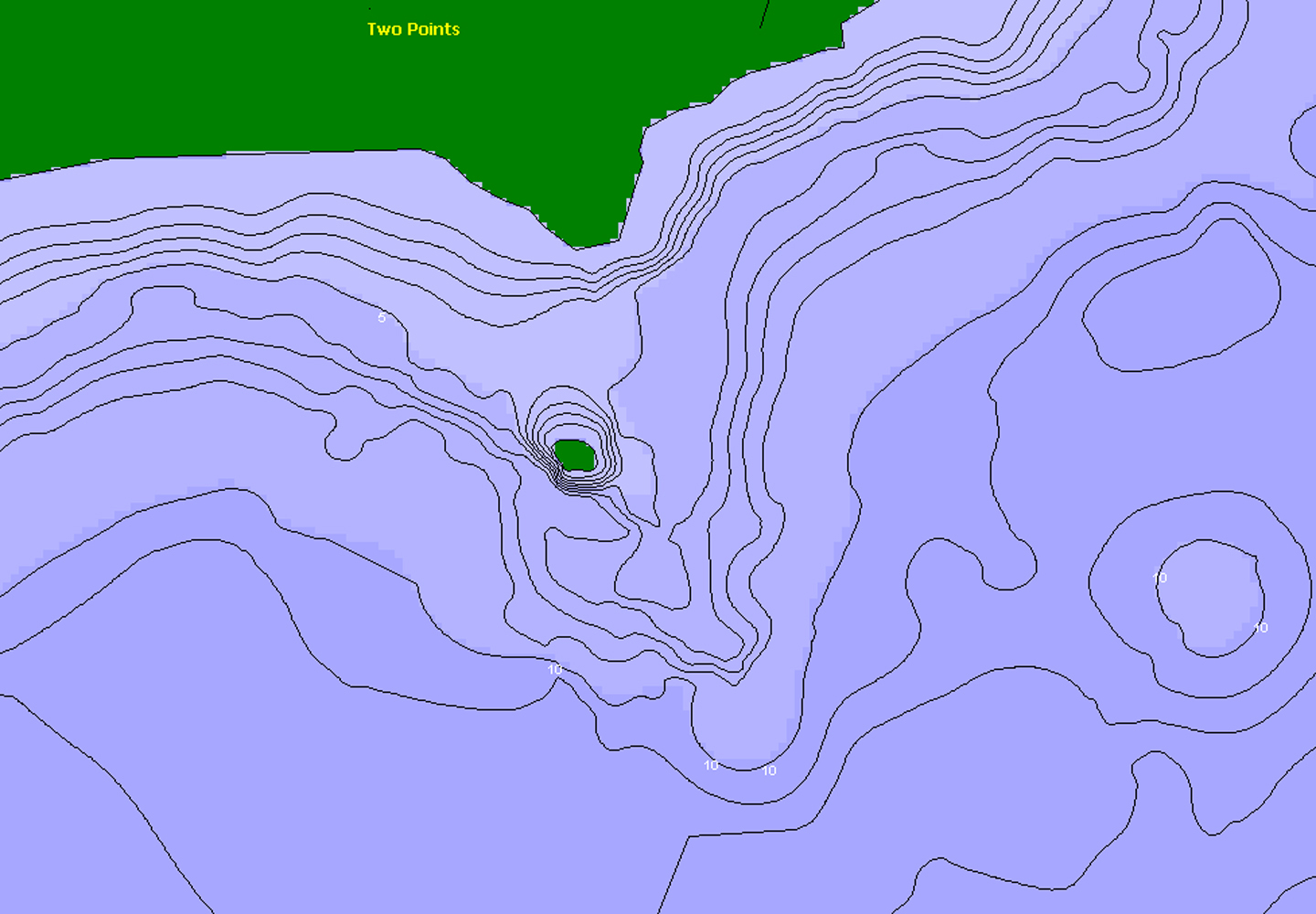

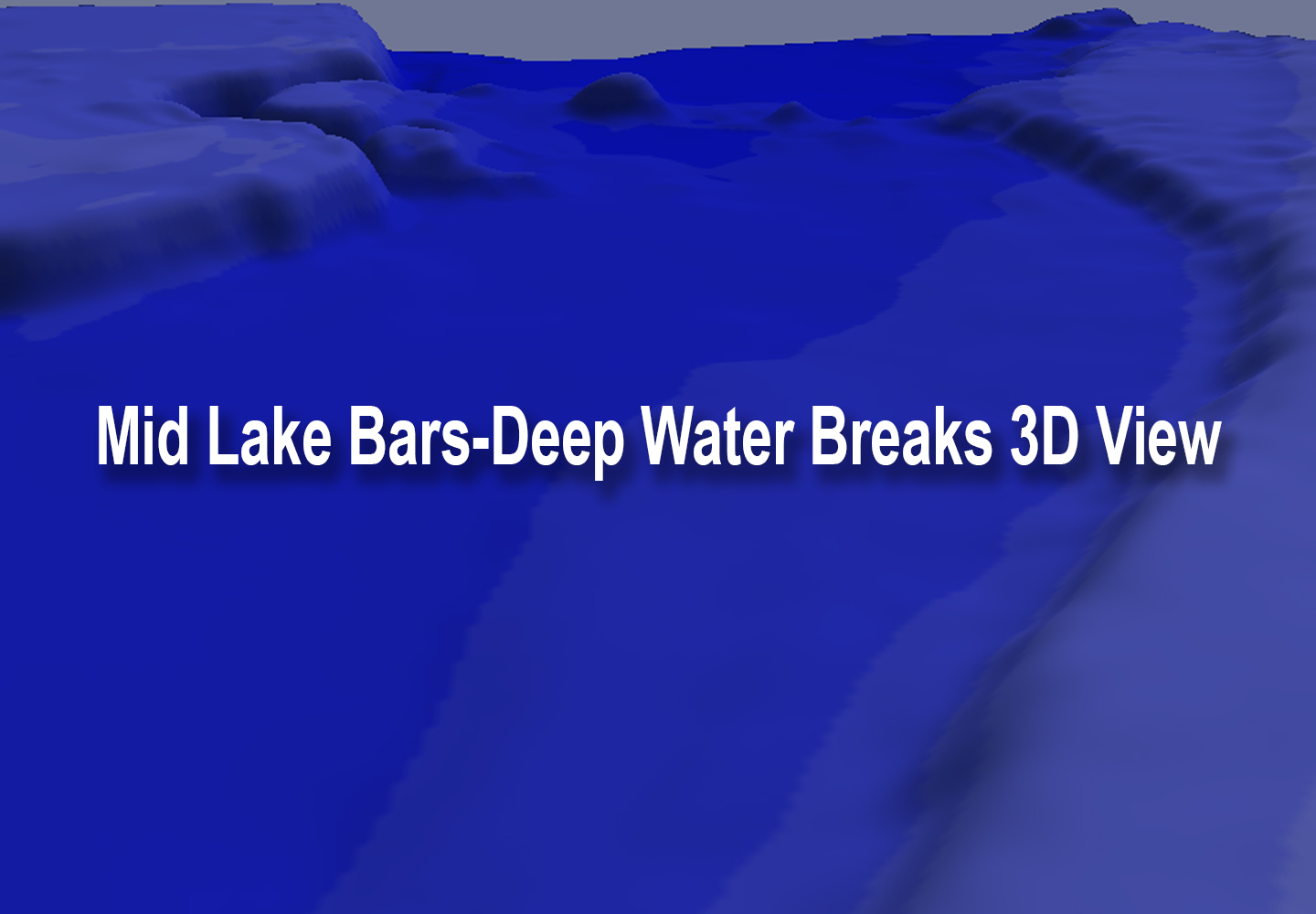

To study mid-lake bars, the most common of all open-water structure, I’ve chosen a map of Lake Winnibigoshish in Minnesota’s Cass County. My reason for this choice is that folks who fish on Winnie frequently use the term “bars” to describe numerous fishing areas on the lake. As you can see, “The Bena Bar” pictured here is actually a steep breakline that leads from the shoreline, all the way out to the lake’s deepest water. Following the edges of the bar in either direction takes anglers on trip around that deep water hole.

To study mid-lake bars, the most common of all open-water structure, I’ve chosen a map of Lake Winnibigoshish in Minnesota’s Cass County. My reason for this choice is that folks who fish on Winnie frequently use the term “bars” to describe numerous fishing areas on the lake. As you can see, “The Bena Bar” pictured here is actually a steep breakline that leads from the shoreline, all the way out to the lake’s deepest water. Following the edges of the bar in either direction takes anglers on trip around that deep water hole.

Depending on which region we fish, anglers may also refer to “bars” using other names. “Deep water breakline”, “mid-lake breakline”, or “deep basin breakline” would all be reasonable alternative choices. Just remember that most every natural lake will have a similar structure that occurs wherever the lakes deepest water meets the surrounding shallower water habitat. The depth will vary by lake too, the image of Winnie shows the breakline from about 14 to 30 feet of water. But in my region, there are several lakes where the “mid-lake bars” straddle a line between 10 and 16 feet deep. There are others, like Walker Bay, or on Cass Lake where the depth ranges deeper, 25 to 80 feet deep for example.

For me, “bars” are typically free of easily identifiable habitat like large stands of weeds, or large rock flats and the like. What they really have going for them is transition between firm bottom, and softer composition of the lakes deepest water. These soft bottom regions produce insect larvae, that in turn attracts bait and other small fish. The attraction for gamefish is the “traps” created by the structure itself. Baitfish, insects and small gamefish that live primarily in open encounter the steep edges and are temporarily trapped on edges of the bars where larger predator species capture them.

For me, “bars” are typically free of easily identifiable habitat like large stands of weeds, or large rock flats and the like. What they really have going for them is transition between firm bottom, and softer composition of the lakes deepest water. These soft bottom regions produce insect larvae, that in turn attracts bait and other small fish. The attraction for gamefish is the “traps” created by the structure itself. Baitfish, insects and small gamefish that live primarily in open encounter the steep edges and are temporarily trapped on edges of the bars where larger predator species capture them.

Fish of all species are attracted to bars at various times of each season. The best fishing typically occurs during mid-summer when the open water food chain is at its peak. Insect hatches that occur when the water warms typically trigger a migration of fish away from shallow water, and into deeper water areas.

Tomorrow, we’ll look at some of the other structures that occur in the lake’s mid-section. But remember my offer, if you’ve been thinking about some other specific situations you’ve encountered on the lake, let me know. We don’t have to complete this series in any particular order, and if needed, I can always come back and explain any gaps in the information.

"Understanding Lake Charts and Mapping" MAIN LAKE FLATS

"Understanding Lake Charts and Mapping" MAIN LAKE FLATS

Flats, and where to fish on them, can drive “structure anglers” like me crazy. Why? Because of the seemingly endless amount of “structureless territory” that they occupy on many of my favorite lakes. Flats are important to anglers because fish, at one time or another, could turn up almost any place on a flat.

Flats, and where to fish on them, can drive “structure anglers” like me crazy. Why? Because of the seemingly endless amount of “structureless territory” that they occupy on many of my favorite lakes. Flats are important to anglers because fish, at one time or another, could turn up almost any place on a flat.

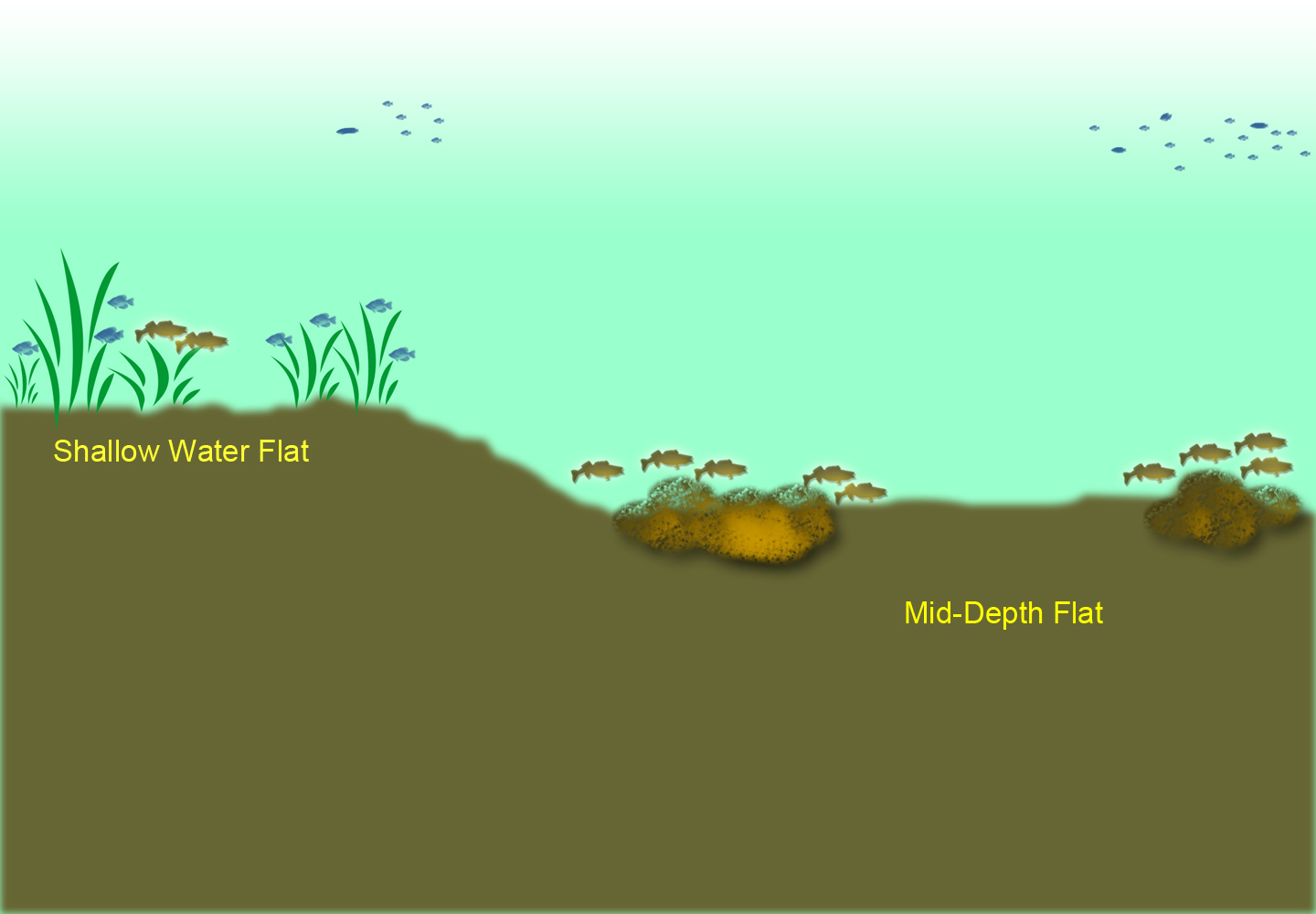

For me, defining a flat is easy; any long, sprawling region of a lake where water depths change little, if at all. When you cannot find a drop off, or a weedline, or come across any fast-changing depths readings on your sonar, then you’re on a flat. Flats can, and often do occur in shallow water, mid-depth range water and again, in deep water.

Depending on the lake, and fishing pattern a writer is describing, you could hear terms like “mud-flats”, “sand-flats”, “weed-flats” and the like. Essentially using the term flat simply refers to an area of unchanging water depth. Any other term attached to it, simply describes they habitat type that is discovered on a given flat.

Forage like insect hatches, minnows, small baitfish and crustaceans attract fish to feed on flats. Seasonal migrations also force fish to cross expanses of flat water as they move from one habitat type to another. The secret to catching fish consistently on flats lies in knowing why fish are there and locating key feeding areas. Avoid the temptation to roam around, using “needle-in-a-haystack” presentations. When you begin discovering isolated “mini structures” like weed patches, rocks, gravel stretches or marl, your fishing luck will improve dramatically.

Forage like insect hatches, minnows, small baitfish and crustaceans attract fish to feed on flats. Seasonal migrations also force fish to cross expanses of flat water as they move from one habitat type to another. The secret to catching fish consistently on flats lies in knowing why fish are there and locating key feeding areas. Avoid the temptation to roam around, using “needle-in-a-haystack” presentations. When you begin discovering isolated “mini structures” like weed patches, rocks, gravel stretches or marl, your fishing luck will improve dramatically.

The accompanying image of both shallow, and mid-depth lake flats illustrates part of what to look for. The problem is that on many flats, structure doesn’t come along as often as it does in my diagram. On some of the lakes where I fish, the distance between structures can be hundreds of yards, sometimes even in miles. Fortunately, there are plenty of lakes with smaller size flats too, and starting small, if possible, is a better way to begin understanding what to look for.

Believe it or not, one great way to learn about flats to look at the habitat in farm country. Here (image right) we have a photo of a single pile of rocks amidst an expansive farm field. The only thing missing is water, because similar structures found in many lakes turn out to be amazingly reliable places to catch fish. Click here for another image, this one featuring a patch of weeds in the center of an open farm field. Again, the isolated nature of the habitat makes pinning down fish an easy task.

Isolated structures, i.e. good fishing spots, have been easiest to locate by using side-imaging. But I’ve located a lot of good ones by simply watching my graph as I motor across the flats. Any time I spy a bump, a patch of weeds or school of baitfish, I stop and investigate, marking the spots if they show promise.

remember my offer, if you’ve been thinking about some other specific situations you’ve encountered on th

e lake, let me know. We don’t have to complete this series in any particular order, and if needed, I can always come back and explain any gaps in the information. ![]() — Jeff Sundin, The Early Bird Fishing Guide Office Cell Call or Text 218-245-9858 or Email

— Jeff Sundin, The Early Bird Fishing Guide Office Cell Call or Text 218-245-9858 or Email

Understanding Lake Charts and Mapping "Weed Lines, Weed Flats and Weed Mats"

Understanding Lake Charts and Mapping "Weed Lines, Weed Flats and Weed Mats"

The search for definitions about weed lines, weed patches and fishing in vegetation was part of the original reader Q&A that got me started on this series about charts, maps and fishing terminology. Fishing in weeds is a big topic and warrants an entire book of its own. In the interest of keeping the discussion simple though, I’ll offer you some general guidance about the definitions, maybe not so much detail about how to fish in them

The search for definitions about weed lines, weed patches and fishing in vegetation was part of the original reader Q&A that got me started on this series about charts, maps and fishing terminology. Fishing in weeds is a big topic and warrants an entire book of its own. In the interest of keeping the discussion simple though, I’ll offer you some general guidance about the definitions, maybe not so much detail about how to fish in them

Submerged vegetation varies not only from lake to lake, but from one region of the Midwest to another. The underwater grasses that I discover in lakes within my home territory may not even exist in yours, and vice versa. So, knowing that I can never address every definition of weed formations in your lake, take my advice and modify it to fit your needs. Vegetation that you encounter will in some way be similar to the varieties that I describe here.

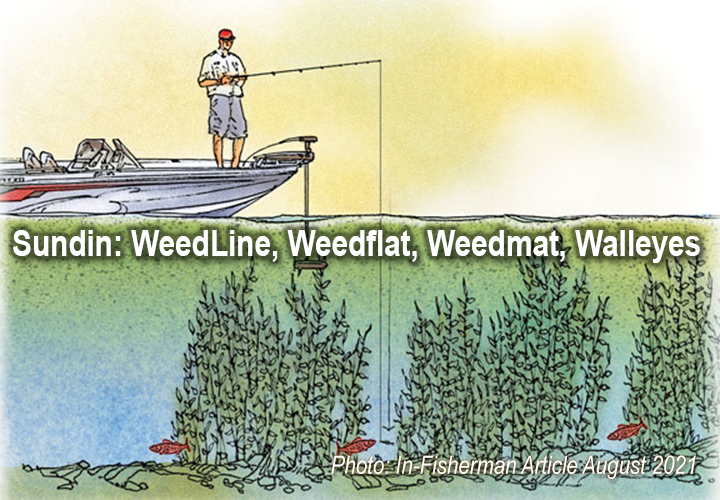

A “weed line”, to me, refers to the edges of a formation of vegetation that can be easily seen and followed. An example in north central Minnesota might be a stand of coontail that grows along the edge of a steep drop-off along the shoreline, or other mid-lake structures. Bulrush, eelgrass, and northern milfoil are more examples of grasses that I’d encounter in my home territory. Weed lines can be fished in a number of ways, including drifting, casting lures, trolling or stationary fishing using slip floats.

A “weed flat” in the lakes I fish are places where shallow water has submerged vegetation growing in patches that cover an expanse of territory. What makes the “weed flat” different than a “weed line” is the absence of a well-defined edge, or easily identifiable depth change. Sometimes, growth will start and stop at random intervals as we travel across the flats. In my region, broad leaf pondweed varieties, loosely referred to as cabbage weeds, often form patches like these on the flats. Coontail patches are common on flats like these too, and I encounter them frequently.

A “weed flat” in the lakes I fish are places where shallow water has submerged vegetation growing in patches that cover an expanse of territory. What makes the “weed flat” different than a “weed line” is the absence of a well-defined edge, or easily identifiable depth change. Sometimes, growth will start and stop at random intervals as we travel across the flats. In my region, broad leaf pondweed varieties, loosely referred to as cabbage weeds, often form patches like these on the flats. Coontail patches are common on flats like these too, and I encounter them frequently.

Weed flats that have sparse patches of vegetation can be fished using trolling presentations. More densely formed vegetation may not allow trolling but can be fished in other ways. As I was brushing up on today’s presentation, I stumbled into some previously published articles that will be helpful. In an In-Fisherman feature article I offered guidance about how to fish for walleyes in this type of heavy weedy cover. In another, a FishRapper report about crappie fishing, I offer advice about catching panfish in heavy patches of weeds on shallow flats.

To learn more about fishing over weedy flats, check these out >> In-Fisherman "Walleye Fishing During Algae Blooms" >> FishRapper "Mid-Summer Weed Patch Panfish.

“Weed mats” are formed by grasses called “emergent vegetation”, weeds that grow up to and above the water’s surface. Matts of vegetation that can be found in my region include lily pads, wild rice and bulrush. From an angler’s perspective, fishing matted vegetation often requires even more specialized presentations than do “weed flats” or ‘weed lines”. The payoff though can worth the trouble, big bass, pike, muskies and walleyes can all come from some of the tightest spaces you can imagine.

“Weed mats” are formed by grasses called “emergent vegetation”, weeds that grow up to and above the water’s surface. Matts of vegetation that can be found in my region include lily pads, wild rice and bulrush. From an angler’s perspective, fishing matted vegetation often requires even more specialized presentations than do “weed flats” or ‘weed lines”. The payoff though can worth the trouble, big bass, pike, muskies and walleyes can all come from some of the tightest spaces you can imagine.

Whenever I research “new lakes” to fish in Minnesota, I log in to the MN DNR website. For random searching, I use their recreation compass, an interactive map that allows me to click and search any lake that looks interesting.

Clicking the link takes me to a another section of the MN DNR website called ‘the lake finder” where I can read all about the lake, including the "Aquatic Plant Survey" which reports the vegetation types found the lake. Knowing what varieties of weeds are present, then allows me to make some educated predictions about the lake’s cover, and how to prepare for fishing it. Once I know which weeds are in the lake, I can look at the map to find places where those varieties are likely to grow.

In your region, use the same concept, but tailor it to the types of vegetation found most often. Once you know which weeds grow on the flats, which ones like the steep breaklines and which ones grow above the surface, you’ll be off and running.

Rember too that references to fishing in and around the weeds are plentiful in the fishing reports pages. May I suggest trying an internet search for more articles about species specific locations and presentations? Another way to find seasonal information is to check out the archives of previously published reports and articles. I’m sure you’ll find some helpful information there too, but if after checking the archives, you still have unanswered questions, you know where to find me. ![]() — Jeff Sundin, The Early Bird Fishing Guide Office Cell Call or Text 218-245-9858 or Email

— Jeff Sundin, The Early Bird Fishing Guide Office Cell Call or Text 218-245-9858 or Email

Understanding Lake Charts and Mapping "Breakline Drilldown A Closer Look"

Understanding Lake Charts and Mapping "Breakline Drilldown A Closer Look"

I think we’ve laid the groundwork for answering Richard Mullet’s January 22, 2025 Q&A about defining lake structures and terminology. Today, I think we can drill into some more specifics about the topic of “break lines.”

I think we’ve laid the groundwork for answering Richard Mullet’s January 22, 2025 Q&A about defining lake structures and terminology. Today, I think we can drill into some more specifics about the topic of “break lines.”

Knowing what a breakline is does give us a common vocabulary that allows us to share information with our fellow anglers. It’s great when somebody gives us a “hot tip” about catching fish in Lake Wishiknew, somewhere along a shoreline break, or on mid-lake structures and the like. But how can anglers, like Richard, pick up a paper map, or fire up his Lakemaster chart and find their own spots that might be productive?

Let’s take a look at one of the scenarios I look for when I’m preparing to fish a “new” walleye lake.

The image of the Lakemaster chart (upper left) shows the kind of spots I’m looking for on a map. The large mid-depth flat lays adjacent to deep water on one side, and adjacent to shallow water on the other. There are a couple of points, a couple steep breaklines and some vegetation. The combination of habitats gives fish numerous options for both feeding and resting. Admittedly, not every lake will offer up ideal scenarios like this one, but I think most lakes have something close.

Once I've researched a map and find a few interesting areas to form a game plan, I look at the local weather. I've created some graphics that illustrate common scenarios related to weather influences on walleye behavior. Click on the highlighted text links to view the full size images.

Active Walleyes - Stable weather means that baitfish, insects and small gamefish will inhabit shallow water. With a stable feeding environment, gamefish like walleye will move into position nearby to take advantage. In my illustration, I highlighted some cabbage weed beds that I’ve fished many times over the years. When the weather is stable and the walleyes are active, they move into the weeds, inhabiting not only the outer edges, but often the shallow inner weed edges hold some walleyes too.

Neutral Walleyes - When the weather isn’t stable, or during midday when walleyes are less active, they tend to gather further away from the weed patches. The term “neutral” best describes walleyes attitudes about feeding, they will strike, but are not voracious. Now, deeper points and steeper breaklines in the mid-depth range hold fish. In this illustration, the key depths usually range between 12 and 20 feet. But the depths will vary depending on the lake you select. A good rule of thumb is to check the points and breaklines that lead toward the lakes deepest water, but not all the way down to their deepest points.

Negative Walleyes - Deep breaklines, or open water is where many walleyes go when their feeding mood is negative. Sometimes, a small portion of the population will also “hunker down” in weeds too. Walleyes hold on deep breaklines, deep points or suspended near, but not on points leading into the lake’s deepest basin. While these locations are ordinarily associated with “negative” fish, there are occasions when deep structure holds walleyes that are active and feeding. Insect hatches during the summer peak, seasonal transitions from shallow to deep habitat and the presence of open water forage species could attract feeding walleyes into deep water.

Okay, so we’re still a long way from any comprehensive strategy to catch fish every time we visit a lake. But in the spirit of Richard’s original question, we are building a solid base of knowledge about how to look at a map and choose some places to target fish. Tomorrow, I’ll offer more thoughts about some common mid-lake structures that we haven’t covered yet. ![]() — Jeff Sundin, The Early Bird Fishing Guide Office Cell Call or Text 218-245-9858 or Email

— Jeff Sundin, The Early Bird Fishing Guide Office Cell Call or Text 218-245-9858 or Email

Maps and Charts 101 | "Wrapping the Wrap-Able" Mid Lake Humps

Maps and Charts 101 | "Wrapping the Wrap-Able" Mid Lake Humps

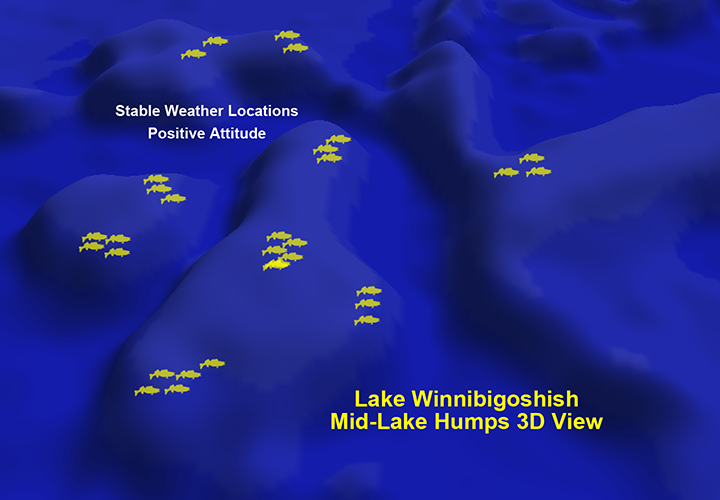

Today’s installment marks the end of my Mapping and Charting 101 series. The topic, mid-lake humps, wasn’t included in Richard Mullet’s original list of questions, but it’s only logical to include it as we wrap up. So, let’s talk today about humps in general, and then use them to practice some of the terminology we discussed this past week.

Today’s installment marks the end of my Mapping and Charting 101 series. The topic, mid-lake humps, wasn’t included in Richard Mullet’s original list of questions, but it’s only logical to include it as we wrap up. So, let’s talk today about humps in general, and then use them to practice some of the terminology we discussed this past week.

“Humps” differ from the January 22, 2025, topic “breaklines and bars” in that mid-lake humps are free-standing structures, not shoreline related.

“Humps” may also be called reefs, sunken islands or mudflats; names vary by region. No matter the nicknames, their common feature is that they do not connect to the main shoreline. Depending on the size and structure of your favorite lakes, they could be located very close to the shoreline, or in larger water bodies they could be found miles away from shore, in open water.

Also, depending on the structure of your lake, their depths can vary too. One of my favorite lakes features humps that top off in 10 feet of water and are surrounded by 16 to 20 of water. Another one of my favorites, Lake Winnibigoshish, has numerous humps that top off in 16 to 20 feet, and are surrounded by 20 to 35 feet. As long as there is a noticeable contrast between shallower and deeper water, the structure meets the definition.

Mid-lake humps tend to be most productive for walleyes during the “summer peak” period. In my area, that can start as early as Memorial Day and typically lasts until water temperatures begin cooling in or around August. Weather influences both the behavior and pin-point locations of fish that are “using” humps at any given time.

Stable Weather encourages feeding activity and the most aggressive fish move high onto the structures. You’ll locate fish high along the upper edges of the breakline. Many fish move even higher on the structure, spreading out across the top, roaming and feeding freely.

Mixed Weather tends to force fish away from the upper portions of the hump. Now they move deeper but continue to hold tight to the structures along the breakline. Some will be found on the deeper points while others move into the turns and corners. It’s common for these neutral, or semi-negative fish to be located close to the bottom, where the breakline meets the deepest water.

Unstable weather, like post storm cold fronts, or bright, windless days can force fish into a negative feeding mood. When that happens, structures that were filled with fish one day, are barren the next day. When you’re looking at a blank sonar screen and can’t find fish anywhere, you’re liable to find them suspended nearby, over the deepest water. Walleyes are still related to the structure but are not holding directly on it. When walleyes move into open water they do not typically move deeper toward the lake bottom. Instead, they hold their previous depth, wherever they were holding on the structure, and move horizontally over the deeper open water. In this example, walleyes can be found anywhere from 6 to 12 above the bottom.

Okay, by now we’ve touched on most of the most common scenarios that an angler could encounter while fishing most of North Central Minnesota territory. I broke down a list of questions from Richard Mullet’s original email and turned them into a bullet point list. I’ve linked each question back to the section where the answers are provided. So, throughout the fishing season, I’ll be able to refer back to this section for definitions, graphics and refinements.

The beauty of producing my own material and publishing my own web content is that I can add content whenever it’s needed. So, please do let me know your thoughts. Did I miss anything, do you have more questions, was this too boring for you, or would you like more info like this? Getting in touch with me is easy, follow any of the links you see here. ![]() — Jeff Sundin, "The Early Bird Fishing Guide" | Office Mobile (Call-Text) 218-245-9858 | Email | Follow on X | Follow on Facebook

— Jeff Sundin, "The Early Bird Fishing Guide" | Office Mobile (Call-Text) 218-245-9858 | Email | Follow on X | Follow on Facebook